Ally McIntosh's Carne Golf Links Essay

After many months of waiting, Ally McIntosh has finally submitted a piece on Carne Golf Links for your enjoyment

Ally McIntosh Biography

Ally McIntosh has a background in engineering, project and construction management. As a Scotsman who settled in Ireland, he grew up on the links and has a deep-rooted love and understanding of the traditions and history of our best golf courses. Graduating as a golf course architect through the EIGCA education program, he set up McIntosh Golf Design in 2010 and was given the opportunity to create the new nine holes at Carne Golf Links as his first lead project. In his spare time, he writes freelance for various golf publications from his base in Dublin and plays most of his golf at Portmarnock.

Ally’s Essay first appeared in Golf Architecture A Worldwide Perspective Volume 7 which is Published by Full Swing Golf Media and edited by Paul Daley

Carne Golf Links

I never had the good fortune of meeting Eddie Hackett. But I’m constantly crossing paths with those that knew him well; and without exception they recount unfailingly positive anecdotes about the man and his methods; of his spiritual nature, his generosity and his determination to introduce small Irish communities to the pleasures that golf can provide. He built more links courses than any other designer of the twentieth century, all in Ireland, most along the length of its western seaboard, from the ring of Kerry in the south to the extreme tip of northern Donegal.

Other than Waterville, perhaps his most famous design was also his last, the Carne Golf Links on the Mullet peninsula in County Mayo. In terms of topography, it is certainly his biggest and I’m far from alone in believing it his best. Situated just 3 km west of the area’s main market town of Belmullet, Carne is located in an incredibly romantic and less travelled corner of the country, rich in history and high on beauty. Its genesis is a story oft-told but it’s safe to say that without Eddie Hackett’s low budget approach to design and construction, the course would have never made it to opening day.

The parcel of land given to Hackett to lay out the original eighteen holes was 260 acres of the wildest, untamed dune scape that I have ever seen. Over the centuries, most dune systems form in a regular order, a series of ridges created parallel to the shore. Not so the sand hills at Carne which appear in a random and chaotic fashion, utterly unique and intriguing. As it did with me, the land wowed Hackett on first sight but it also presented him with some major structural challenges. Given the budget constraints and Hackett’s overarching philosophy which demanded that very little of the natural soil should be moved, he decided at the time – perhaps sensibly - to use the highest and most severe dunes only for his back nine, routing the front nine on a square parcel of undulating land found to the east of the eventual clubhouse position. There is excellent golf to be found on these early holes, the par fours at 3, 6 and 9 amongst them; but for most visitors to Carne, the experience builds to a climax that is the sheer spectacle of the back nine, in between the huge hills and within sight of the Atlantic Ocean.

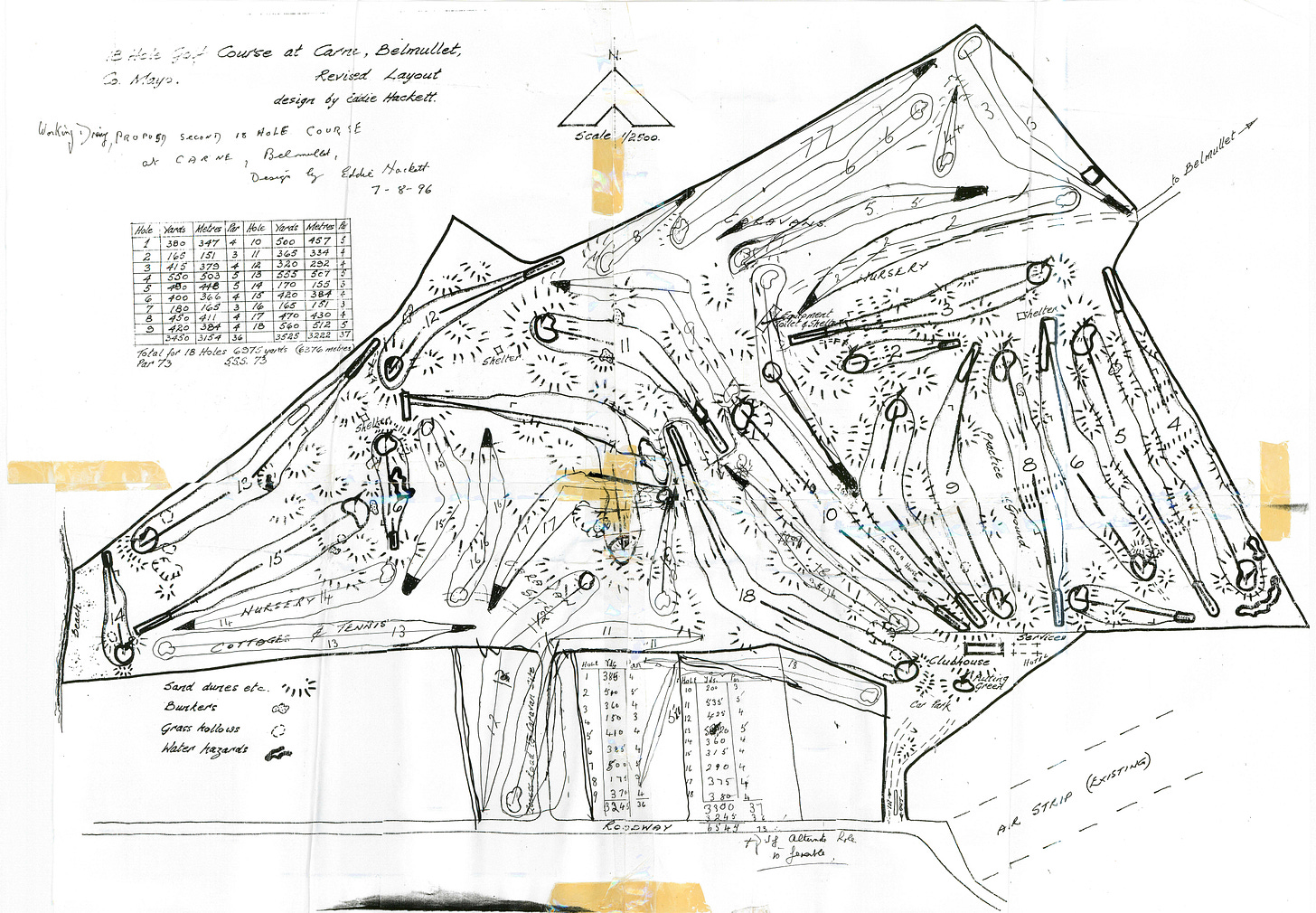

From Hackett’s words at the time of opening, it was clear that he was incredibly happy with the finished golf course, even saying in a rare show of pride that “ultimately, there will be no better links in the country, or I doubt, anywhere”. But some of the unused land clearly prayed on his mind, because in late 1996, only two months before he died and unable to coerce his legs in to carrying his body back over those massive dunes one final time, he found himself sitting again in the Carne club house, putting together from memory a possible routing for a further eighteen holes (see illustration). And although it never came to anything; and in truth wasn’t even a workable solution; it was the spark that ignited the eventual design of a new nine holes and why I found myself in Carne fourteen years later running around those same dunes tasked with that very job.

The club kicked off the new nine in earnest as far back as 2004 when architect and overseas member Jim Engh put together an initial master plan. Some early work was carried out but the routing was never set in stone and through one reason or another, the project faltered and then effectively halted. It never went away though; and with my appointment arising from a clear vision that tied with Eamon Mangan, Carne’s tireless director and construction supervisor, we started afresh in 2010, all of us keen to remind people that given the right land and mentality, world class golf courses can still be constructed for much smaller sums than the “industry” would have us believe.

In order to do this, we would follow Hackett’s mantra for treating the existing contours and ground as hallowed turf, displacing it as a last resort. After all, the build would be done by the local green staff using just one six tonne excavator and dumper so this was not only desirable but a practical necessity. Given that the new holes would traverse the largest dunes on the entire property, making the course compact and playable was therefore going to be the biggest challenge. With golf courses, I’m a traditionalist and my values have been shaped by growing up in Britain and Ireland. So, for me, golf is a walking game and the flow of the routing and proximity of tees to the previous greens should be prioritised, even if this means sacrificing the occasional individual moment. With Carne, this was a difficult task because of the height and severity of the dunes but the major routing changes were focused within these parameters. A case in point was the introduction of the par-3 second hole which allowed us to stay high on a dune ridge before descending again, thus eradicating a large climb from the previous plan. It just so happens that this is an iconic and dramatic hole as well, so there was a double positive in the decision. Ensuring we had enough width was another challenge. Links courses are windy places and sometimes the natural valleys just aren’t wide enough to be suitable. So the final hole corridors had to be of a scale that would provide fun for everyone to get round.

There was a further reason why I was keen to follow Hackett’s low impact philosophy. In many ways, Eddie was the ultimate minimalist designer and that was why he was the perfect fit for projects with such serious economic constraints. But it is also why his courses are so difficult to date to any particular era, least of all a “modern” one. I knew that if we followed his methodology, the new nine would intermingle organically with the original holes and the final twenty seven would feel part of one interchangeable golf course. Once we worked to that ethos, it gave us license to introduce some different challenges in the more detailed elements of the design. For example, I wanted the bunkering to play a more strategic role than on the original eighteen; so despite numbering only sixteen in total, each bunker is near the ideal line of play and extracts a severe penalty from those that find it. Additionally, we were adamant that we needed to bring some interest in to the greens. When you have huge, erratic dunes, it makes no sense to have perfectly flat greens at the base of them: nature doesn’t behave in this fashion. So in some cases, we left original green undulations in place but more often, with the help of my partner James Coughlan on the excavator, new ones were constructed to replicate the style of the surrounding landscape.

Our method for actually building those greens was simple: Work with the local materials. That meant stripping the organic topsoil – or “black sand” – and shaping in the white sand underneath. Then we relayed the very same root zone and finished the green with sod cut from a turf nursery on site. We had no drainage worries and therefore, aside from irrigation that was put in on the greens and tees only, we had no material costs either. Only two of the putting surfaces needed fill brought in from elsewhere on site and given the slow process that this entailed, it was key to balance any earth movement we did in to very small compartments. Not only did this methodology provide a cost-effective build but it also meant that we weren’t introducing foreign soils and grasses in to the dune system and this has undoubtedly assisted in that “been there forever” final effect that we were searching for.

The whole team is tremendously proud of the end result. The Kilmore nine had its soft opening at the end of summer 2013 when all present played the composite routing that seamlessly intertwines the new holes with the current Hackett back nine. The comments from all – even those that had questioned the sanity of continuing with the project in the midst of an economic crisis – were overwhelmingly positive. I knew we had created some of the most awe-inspiring holes on the links, each one individual and unlike any of the other 26; but what pleased me most was listening to the members who proclaimed their amazement that these holes took them over areas of the dune system that they never even knew existed. And how the composite course we played brought a sense of togetherness as other groups could be seen dotted all over the distance, snaking in and out of this fantastic lunar landscape. That social element on the course manifests most clearly off it in the community spirit and genuine, hospitable nature of the Mayo people who represent the glue that binds the Carne experience as one, special whole.

The strongest adhesive of all, however, was provided by Eamon Mangan, without whom these nine new holes would have remained a pipe dream of the original designer, long since passed. I may never have met Eddie Hackett but I consider myself very fortunate to have worked alongside Eamon. In one hundred years’ time, when Carne is no longer considered a new course but a “classic”, then justice will only be served if these two men are remembered in the same breath.